This article was co-written with an artificial intelligence—the kind now helping companies replace warehouse workers, copywriters, and analysts alike. It seemed fitting.

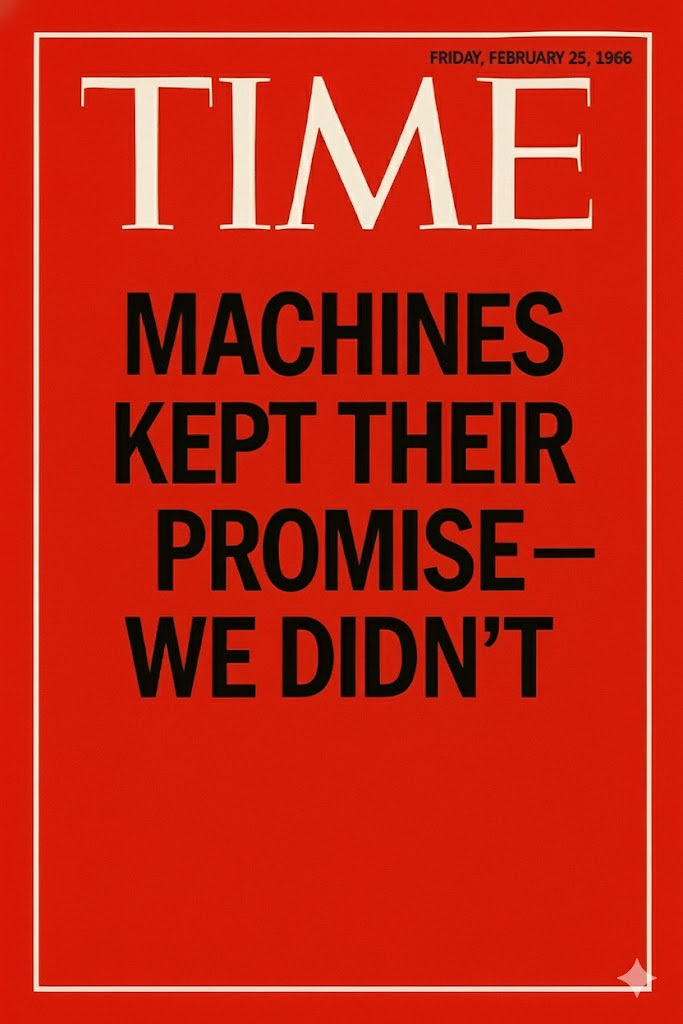

Sixty years ago, in February 1966, TIME magazine made a prophecy. "By the year 2000," the editors wrote, "machines will be producing so much that everyone in the U.S. will, in effect, be independently wealthy." Automation, they promised, would make labor optional and leisure meaningful.

The machines kept their promise. They did make more—faster, cheaper, endlessly. But we didn't become independently wealthy.

To understand why, we traced the story from 1966 to 2025—through economic data, historical forecasts, and a Reddit thread about Amazon replacing 600,000 workers with robots. What followed was a strange collaboration: curiosity and unease met perfect recall and zero emotion. Together we built a conversation between optimism and disillusionment, between TIME's mid-century prophecy and Reddit's modern despair.

The Numbers Don't Lie

The data are simple, brutal, and long ignored.

The Divergence

U.S. Productivity: 179 → 406 (1966-2025)

Worker Pay: 165 → 253 (same period)

The Gap: Productivity +87% vs. Pay +33% since 1979

Median Income: $59,770 → $84,000 (40% growth over 60 years)

According to the Economic Policy Institute, U.S. productivity has more than doubled since 1966. Typical worker pay crawled upward by barely half that amount. Between 1979 and 2025, productivity soared 87%; hourly pay rose only 33%.

Median household income—adjusted for inflation—went from $59,770 in 1966 to $84,000 in 2025. Nearly all that growth happened before 2000. Since then, incomes flatlined while corporate profits and shareholder returns exploded.

The data are the ghost of TIME's optimism. The machines really did make more. The prosperity simply stopped trickling down.

AI: "The productivity-pay divergence is structural, not cyclical. Ownership captured the surplus; labor lost the transmission mechanism."

Human: "Translation: the robots got efficient, and we got left behind."

In the 1960s, the deal was simple: if you worked, you shared in growth. But after the 1970s, technology's dividends flowed elsewhere—to capital, code, and intellectual property.

The 1966 futurists assumed abundance would be shared automatically. Progress, they believed, was a rising tide. What they missed was power. Automation created wealth, but the structures deciding who owns the robots, data, and platforms concentrated that wealth.

Reddit's Wake

Fast-forward to 2025. On Reddit's r/artificial, a post titled "Amazon to replace 600,000 US workers by 2033 with robots" set off a digital riot.

"Eventually companies will run out of customers," wrote one user. "Universal Basic Income," someone replied. "Not without revolution," came the answer.

For two days, hundreds argued whether automation would free humanity or hollow it out. Some saw UBI as the inevitable safety net. Others called it a bribe. A few imagined robot customers buying from robot sellers—an economy with no humans left in the loop.

The thread felt less like a conversation and more like a wake. A collective mourning for an economic model that no longer believes in its workers.

AI: "Sentiment analysis: dominant tone equals fatalistic. 72% negative valence toward automation."

Human: "That's one way to say people are scared."

The Reddit debate reads like the emotional transcript of the last fifty years of economic data. When one user writes, "They'll use UBI to keep you poor," they're articulating what economists call capital-biased technological change. When another says, "They don't need us anymore," it's the folk version of the productivity-pay gap.

The crowd may not cite the Economic Policy Institute, but it feels the same math in its bones.

When asked why the prediction failed, the AI answered without hesitation: "Because technological capacity increased faster than distributive mechanisms evolved."

A sterile truth. But a real one. The technology was never the problem. The governance was. We optimized for efficiency, not equity—and got exactly what we optimized for.

If Amazon replaces 600,000 workers, it will be another chapter in the same story: progress without participation. The question isn't whether automation happens. It's whether the benefits are shared.

We can tax robots, fund UBI, or build cooperative AI systems. But the harder work is philosophical: redefining human value when productivity no longer measures worth.

Human: "The machines kept their promise."

AI: "Humans did not."

It sounds harsh, but it's an observation about systems, not people—about how we designed the rules of distribution, not the capacity for abundance.

This essay is both subject and symptom. A machine helped write it—the very type of intelligence now displacing writers, analysts, and warehouse staff. And yet, writing with it felt less like surrender and more like synthesis. A glimpse of the partnership those 1960s futurists imagined but never built.

Maybe the next age of abundance won't come from replacing humans, but from finally learning how to collaborate with the machines we've already created.

If we can do that—if we can align progress with purpose—then the future TIME promised might still be possible.

Not automatically. Not inevitably. But intentionally.